A few months ago Christian Gerhartsreiter (right), or Clark Rockefeller, made headlines after being found guilty of first-degree murder for a crime which he committed 28 years ago. Gerhartsreiter is an interesting man and a photo in which he appears makes for a very interesting copyright infringement case. (The Guardian/AP)

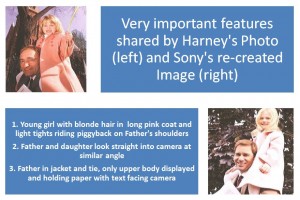

When it comes to photographs, how does one measure whether a copying rises to the level of infringement? This was the question before the court in Harney v. Sony Pictures Television, Inc. and A&E Television Networks, LLC. The United States Court for the District of Massachusetts determined that although the defendants had copied another’s work, the original photo and the re-created image lacked the substantial similarity required to satisfy a copyright infringement claim. The court’s decision was subsequently affirmed on appeal by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit in Boston.

Background:

Freelance photographer Donald Harney approached a father and daughter as the pair was exiting a Boston church on Palm Sunday, April, 2007 and asked to photograph them for a local paper. The young girl, Reigh Storrow Mills Boss, had long blonde hair, wore a pink coat and rode piggyback on her father’s shoulders. Her father, Christian Gerhartsreiter, at the time was presumed to be Clark Rockefeller. He kidnapped his daughter later that year.

Without Harney’s knowledge or consent, the FBI immediately used the photo he had taken of Gerhartsreiter and Boss in a “Wanted” poster. (It is unclear from the documentary record where the FBI obtained the photograph in the first place.) News of the abduction made national headlines and many reports featured Harney’s photograph. Harney did not object to the use of the photo so as not to hinder recovery efforts. Boss was recovered within a week. However, public interest in the story remained high, and this time, Harney licensed use of the photo to several media outlets which sought to investigate Gerhartsreiter’s true identity.

In 2010, Sony Pictures Television, Inc. and A&E Television Networks, LLC re-created Harney’s photograph in a made-for-television movie, “Who is Clark Rockefeller”, to demonstrate the role the photo played in the abduction events. Harney challenged their use of the photo in federal district court, alleging that this use infringed his copyright.

On the ground that Harney’s photo and Sony’s re-created image did not share substantial similarity, the defendants moved for summary judgment. Sony had further argued that inclusion of the image in its docudrama constituted fair use because Harney’s photo had been used in mainstream media.

The Case:

We learn from the First Circuit Court of Appeals that there was neither a dispute in Harney v. Sony Pictures Television, Inc. and A&E Television Networks, LLC regarding plaintiff Donald Harney’s owning a valid copyright in the photo, nor was there any question about whether Sony had copied Harney’s photo. The contested issue in Harney’s infringement claim was simply (or maybe not so simply) whether Sony’s re-created image, in exhibiting the original expression of the former work, could be described as substantially similar to said former work.

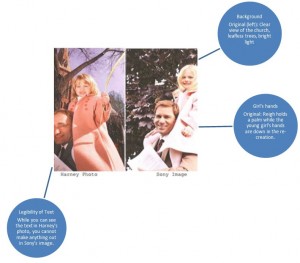

The district court dissected elements of both the original photo and Sony’s re-created image and found that although there were, in fact, copyrightable elements of Harney’s photograph, Sony had not copied any of these.

District Court Judge Rya W. Zobel found that Harney’s photo and Sony’s re-created image clearly shared factual content, but did not share Harney´s expressive elements, and thus the photos lacked substantial similarity. (Images: United States Court of Appeals For the First Circuit via Bloomberg Law)

Federal District Court Judge Rya W. Zobel found that Harney’s photo and Sony’s re-created image clearly shared factual content, but did not share Harney´s expressive elements, and thus the photos were found to be not substantially similar. And, based on this view that the pictures shared only factual or non-copyrightable elements, the court determined that no reasonable jury could find substantial similarity between the works and granted the defendants summary judgment. The case was dismissed.

Consequently, Sony’s fair use claim was never addressed, although the court did note that the defendants used the re-created photo 5 times during the film for a total of 42 seconds and for less than 1 second in one of the 22 television commercials promoting the film, suggesting that the court would have been receptive to a fair use defense as well.

The Appeal:

On appeal, Harney argued that the district court had “over-dissected” his original work and that the court had “misapplied the applicable test for assessing substantial similarity”. The First Circuit Court of Appeals rejected Harney’s arguments, holding that the only element shared between the photos for which Harney could take credit was the positioning of the subjects. The appeals court referred to this as “limited sharing” and concluded that this did not infringe Harney’s copyright.

The Dissection: Details noted here are those upon which the district court based its ruling of lack of substantial similarity. The Court of Appeals agreed. (Images: United States Court of Appeals For the First Circuit via Bloomberg Law)

Although Judge Kermit Lipez, First Circuit Judge for the United States Court of Appeals, notes that Harney “undisputedly produced an original, expressive work”, the appeals court still agreed with the district court that no jury could decide for itself that Sony’s recreated image infringed upon Harney’s copyright in his work. The appeals courts thus affirmed the grant of summary judgment. Furthermore, Hon. Lipez notes that although Harney used aesthetic judgment in his work, the photo lacked expressive elements, more like a candid photograph.

Harney challenged this view on 1709 Blog stating: “This is a man that never wanted to be photographed for obvious reasons. I really had to step outside my comfort zone to convince this man that I needed to photograph he and his daughter for the local newspaper.” As Harney describes it, Gerhartsreiter was reluctant to have his photograph taken and had to be persuaded. Harney told Gerhartsreiter and Boss how to pose, which direction to face and when to smile.

It may seem contradictory to state that Harney’s photo lacked expressive elements while basing a non-infringement ruling on major differences between the two images. The later work is clearly derived from the former, and by that definition alone Harney’s photo should be (in every sense of the word) “original”. Sony obviously posed its photo to suggest the original. What is strangest about the case is the judge’s unwillingness to allow a jury to draw its own conclusion about copying when the suggestiveness (at a minimum) is so obvious.

Other Copyright in Photography Cases

1. Schrock vs. Learning Curve Int’l

Learning Curve International contracted freelance photographer Daniel Schrock to photograph “Thomas and Friends” toy train figures for a project. Schrock offered the defendants use of these photos for future use but they declined. Despite prior disinterest, Learning Curve later used the photos without Schrock´s permission.

Schrock sued Learning Curve for copyright infringement in the District Court for the Northern District of Illinois. Learning Curve appealed, arguing that because the works Schrock had photographed were derivative, his copyright wasn’t valid without permission from the underlying copyright holder. The court dismissed the case and granted the defendants Summary Judgment. Schrock appealed.

Before the United States Court of Appeals Seventh Circuit was whether Schrock´s work was even copyrightable due to the fact that it had been a derivative work (as his photograph featured toys, which are based on a television show, which is based on a book). The court determined that originality would be the litmus test in determining if a photo (derivative or not) could be copyrightable.

Although Schrock’s photograph had been based on an original work, the Court of Appeals held that his photos of the toys “possessed sufficient instrumental original fexpression to qualify for copyright”, specifically relying on the photographer’s testimony about his detailed creative process during the proceedings. The court further held that Learning Curve’s actions were infringing. Art Law Blog called the Schrock decision” an important affirmation of the rights of photographers in their works and the artistic merits of these works”.

2. Leigh vs. Warner Brothers Inc.

Jack Leigh was hired to take a photograph for the cover of John Berendent´s 1994 publication Midnight in the Garden of Evil. When Warner Brothers made a film based on the book years later, they hired another photographer to capture multiple images of the now famous Bird Girl statue, which Leigh had chosen for his photo to represent the story’s tone.

Leigh sued Warner Brothers for infringing on his trademark and copyright through the use of their own images in the film and in the film’s promotional content. According to Photo Lawyer, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Georgia did not deny Leigh’s copyright in his photograph. Rather, the court was faced with determining which elements of his photo were protectable ones and whether those protectable elements had been infringed upon. Leigh’s testimony helped the court to decide that there were in fact expressive aspects of his photos.

Judge John F. Nangle of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Georgia determined that elements of Leigh’s photo and Warner Brothers’ images used in the film and in its promotional material were not substantially similar and granted summary judgment to Warner Brothers. Leigh appealed and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit affirmed the grant of summary judgment for images used in the film.

The Court of Appeals did find, however, that the similarities between Leigh’s work and Warner Brothers’ images used in the film’s promotional material DID share substantial similarity and reversed the summary judgment for this particular claim. The Court of Appeals determined that similarities between these images were significant enough to have a jury decide the question of infringement.

Conclusion

A useful conclusion is difficult from these cases, except to say that owning a copyright will not guarantee you a victory in an infringement claim. And as we’ve seen, courts may dissect, analyze and scrutinize works and, in the end, determine that the differences between a plaintiff’s work and a copycat’s work are just not legally meaningful. Or the court might find otherwise.

The problem is the question of what is copyright subject matter, specified in the Copyright Act, Section 102(a) [http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/17/102], as “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed, from which they can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device.” Section 102(a) goes on to list 8 categories of types of works “literary works”, “musical works”, “dramatic works”, etc., but it is still only caselaw that defines what constitutes “original” in “original works of authorship”. The problem is complicated – or perhaps, highlighted – paragraph (b) of that same Section 102 [http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/17/102], which states:

“(b) In no case does copyright protection for an original work of authorship extend to any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery, regardless of the form in which it is described, explained, illustrated, or embodied in such work.”

So, can the photograph of a particular pose be afforded copyright protection? Who knows? Choreography certainly can be covered by copyright (Section 102(b)(4)), but that might not help much because there’s “original” choreography and there’s … everything else. Where the copying – as in the Harney case – did not actually involve the physical copying of the work itself, there’s still no reason to think that the way a photographer sets up a photograph cannot pass muster as “original”. But just like fair use cases, these seem obviously to be questions that factfinders (i.e. juries) can differ about.

Finally, even if you own a copyright of your photograph, you do not necessarily own the idea or theme associated with it… even if it was your own to begin with.

Many thanks to Andy Mirsky, Principal with Mirsky & Company, PLLC, for his contribution to this post.

Add Comment