United States copyright law was changed substantially in 1976, with changes effective as of January 1, 1978 and forward. The regulatory scheme established as of January 1, 1978 is still (essentially) in effect today, and determines how copyright status is viewed with respect to new works and to existing works.

A. US Copyright Law Pre-1978

Prior to 1978, copyright law granted a copyright of 28 years from the date of a work’s publication with notice (through a required filing of a copyright registration with the Copyright Office). The copyright was renewable after 28 years for a single additional period of 47 years (by filing another renewal copyright registration).

After the expiration of the full 75 years (28-year initial term plus 47-year renewal term), the work went into the public domain. Similarly, upon the expiration of the initial 28-year term, if the copyright owner failed to file a renewal registration, the work went into the public domain. This 28/47 rule (total of 75 years) applied to works that were both author-owned copyrights and “works made for hire”. In terms of length of term of copyright, there was no distinction under the pre-1978 law between author-owned works and “works made for hire”.

B. US Copyright Law 1978 and Forward

Under the law 1978 and forward, 2 categories of rules apply:

- For works published before 1978 and previously subject to the pre-1978 law, the older law’s 28/47 rules still apply, including the requirement that upon expiration of the initial 28-year term copyright owners are still required to file renewal registration to secure copyright renewal – even if the initial 28-year term expires after 1978.

- For works published 1978 and forward:

- For an author-owned work (i.e. not “work made for hire”), copyright runs for a single term of the author’s life plus 70 years and no actual copyright registration is necessary to effect the copyright – that was a big change in the law.

- For a “work made for hire”, copyright instead runs for the shorter of 95 years from first publication or 120 years from creation of the work, whichever expires first.

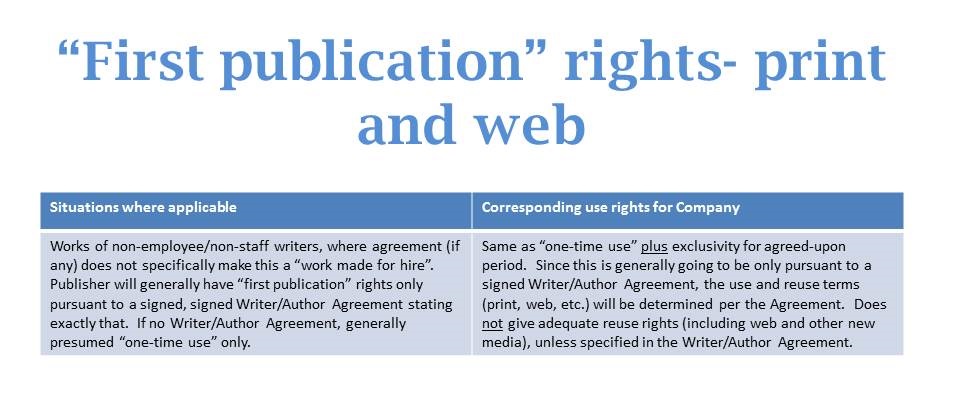

For works published at any time, the question of use rights is determined by whether (a) the work is in the public domain, (b) the work is a “work made for hire” and (c) the work, if author-owned, is the subject of a license or author agreement or similar grant of publishing rights to a publisher, and further, what were the scope of rights actually granted under that agreement. If (a) or (b), the publisher has full use rights (although no longer exclusive if now in the public domain). If (c), the scope of a publisher’s use rights depends on the license agreement or author agreement – if there is one – including “first publication” rights, full assignment of copyright, etc.

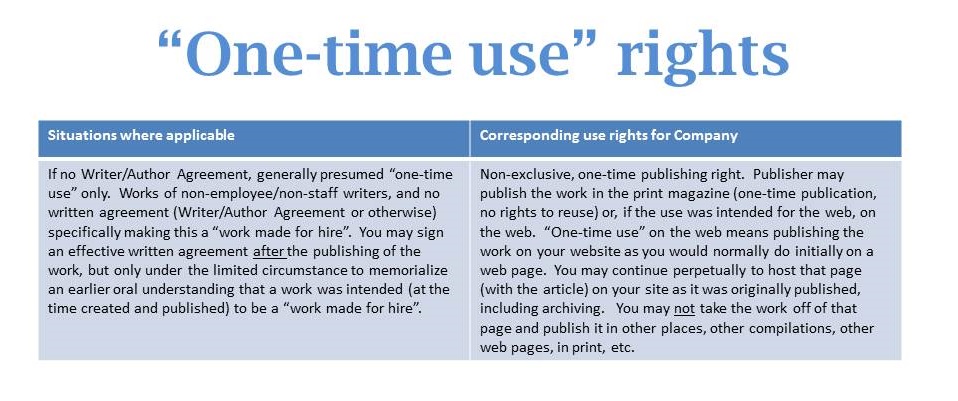

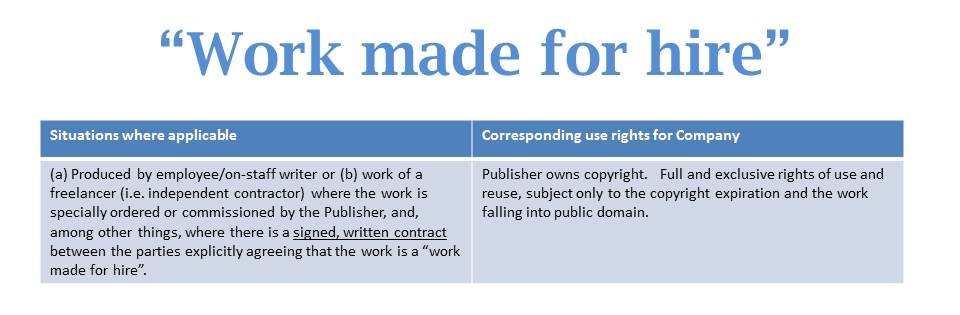

NOTE: In order for a work to be a “work made for hire”, it must be either (a) produced by an actual W-2 employee or (b) the work of a freelancer (i.e. independent contractor) where the work is specially ordered or commissioned by the publisher, and where there is a signed, written contract between the parties explicitly agreeing that the work is a “work made for hire”. For works of freelancers without written agreements, these cannot be “works made for hire”. There is support in the law for situations where a written agreement is signed after the publishing of the work, but only under the limited circumstance to memorialize an earlier oral understanding that a work was intended (at the time created and published) to be a “work made for hire”. A retroactive written agreement to make a work a “work made for hire” is generally not valid.

This is how this works in practice for a publisher:

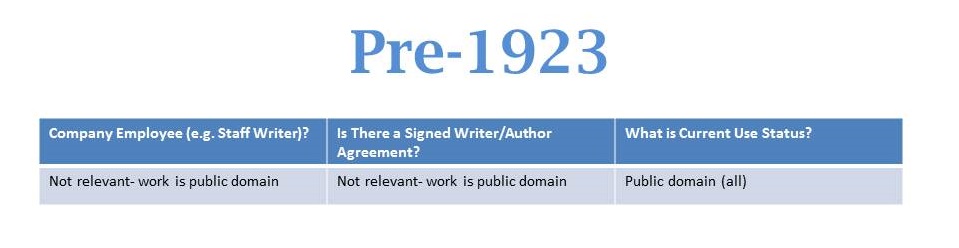

C. Author Works Pre-1923

Copyright has expired for all works published in the United States before 1923. These works were published more than 75 years ago, and thus beyond the expiry of applicable copyright renewal terms. These works are in the public domain. NOTE: Full use of public domain works, while permitted, is not exclusive use.

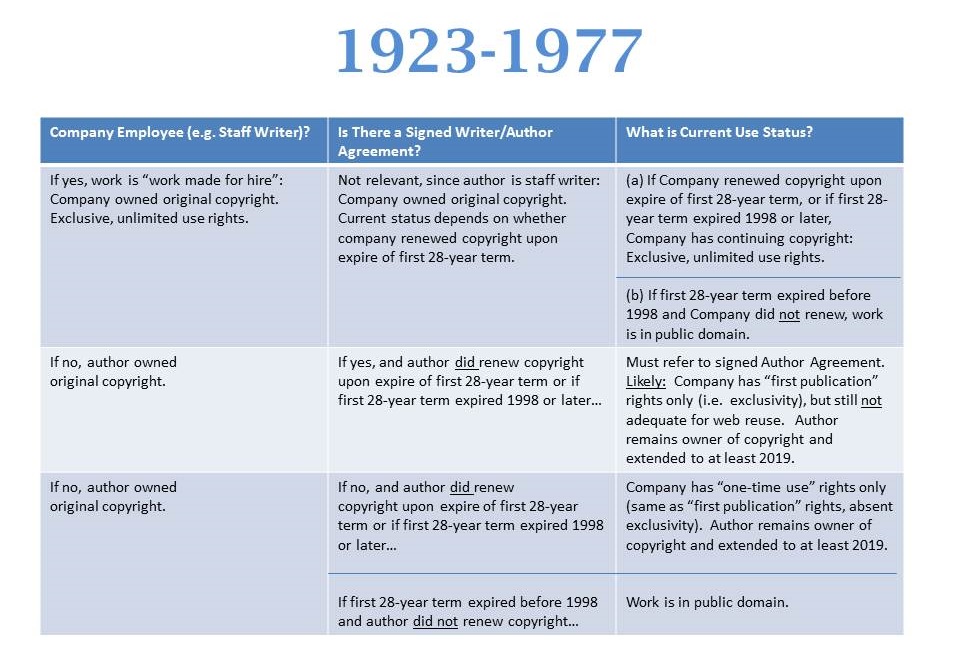

D. Author Works 1923-1977.

D. Author Works 1923-1977.

2 situations:

1. Employees (e.g. staff writers) (1923-1977). Because staff writers are typically W-2 employees, works of these writers would be deemed – automatically – “works made for hire”, and thus copyrights would have been initially owned by the employer. If copyright registration was never filed, or if it was originally filed but not later renewed, these works would be in the public domain. An exception is for copyrights that would have expired in 1998 or later, which were extended by Congress until at least 2019 (discussed below). Thus, copyright remains either owned in full by the employer, or in the public domain, in either of which cases the employer may use in full. NOTE: Again, full use of public domain works, while permitted, is not exclusive use.

2. Non-employees/non-staff writers (1923-1977), either (a) no author agreement or (b) an author agreement, but presumably inadequate to encompass web, electronic, other new media. As to works of these writers, the authors, assuming they filed their copyright registration, would have owned the original 28-year copyrights and rights to renew for an additional 47-year term. The employer would have had whatever rights were originally granted under the author agreement: Typically, one-time use rights. And either because the employer had no writer/author agreement, or because the writer/author agreement inadequately covers new media, the employer would have had no adequate rights to new media use. “One-time use” means: the employer may publish the work in the original intended use (e.g. a print magazine or on the web if the use was intended for the web). But since the rights granted would not have been exclusive for the employer, the author may continue to do whatever he/she wishes with the work, including permitting other publishers to publish the work simultaneously. Exclusivity is the major difference between this and a “first publication” right.

To illustrate:

As noted above, copyright has expired for all works published in the United States before 1923. 1923 is significant because that was 75 years before 1998, when Congress amended the Copyright Act to provide that no new works would fall into the public domain until 2019. In 2019, public domain for works published in 1923 would kick in, with 1924 next, then 1925, and so on. In other words, as to all works from 1923 and later that had not already fallen in the public domain by 1998, copyrights were extended until at least 2019.

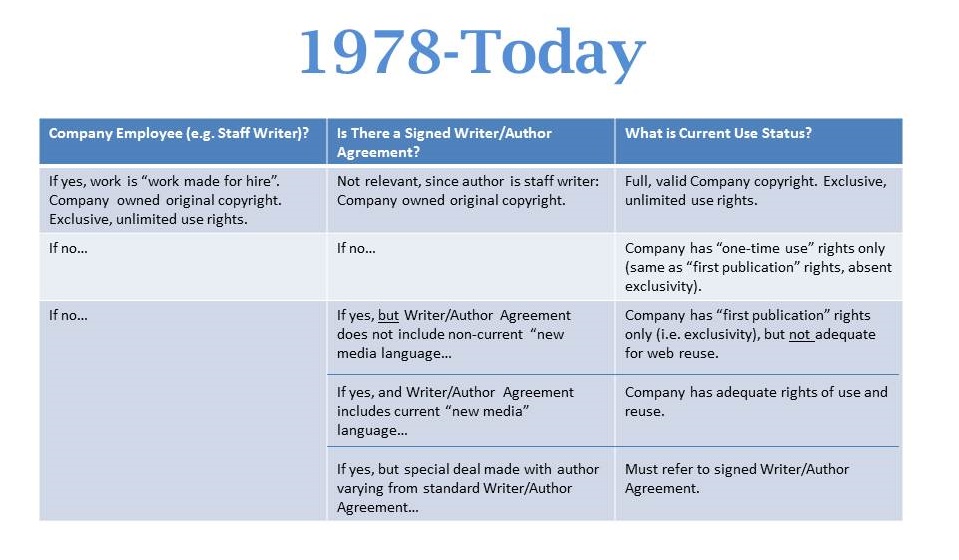

E. Author Works 1978 and Forward

For works from 1978 and forward, these works will all still be under copyright. Same 2 situations as above (but different results), plus the third situation of web publishing. This is illustrated here:

1. Company staff writers. Works of staff writers (W-2 employees) would again be deemed “works made for hire”, and thus copyrights would have been initially owned by the employer. The employer need not have filed copyright registration in order to effect copyright ownership. Copyright runs for the shorter of 95 years from first publication or 120 years from creation of the work, whichever expires first. Thus, copyright remains owned in full by the employer and the employer may use in full.

1. Company staff writers. Works of staff writers (W-2 employees) would again be deemed “works made for hire”, and thus copyrights would have been initially owned by the employer. The employer need not have filed copyright registration in order to effect copyright ownership. Copyright runs for the shorter of 95 years from first publication or 120 years from creation of the work, whichever expires first. Thus, copyright remains owned in full by the employer and the employer may use in full.

2. Non-staff/non-W-2 employee contributors, 3 possibilities: (a) no author agreement or (b) an author agreement, but (same as above) presumably inadequate to encompass web, electronic, other new media or (c) an author agreement, incorporating language similar to “electronic form and in any and all formats and media now known or hereafter developed”. As to all works of these writers, copyright is owned by the authors and runs for a single term of the author’s life plus 70 years (and no actual copyright registration is necessary to effect the copyright). As to situations (a) and (b) above, the employer would have had only limited one-time use rights – in the original intended use itself (i.e. a print magazine, or one-time on a website, or whatever. But typically not web or other electronic use. This is obviously limiting, especially for electronic reproductions and web use. Thus, either because the company had no writer/author agreement, or because the writer/author agreement inadequately encompasses new media, the company would have had no further rights of use in situations (a) and (b) above.

As to situation (c) above, the company would have adequate rights of use and reuse encompassing the web and other electronic formats. So, as to these works, use rights depend on to what extent the current writer/author agreement has been used.

3. Regarding Web: non-staff writers, non-“works made for hire”. For company staff writer works, “work made for hire” rules apply to web same as print. No limitations. If the work was submitted for publication in the print magazine, and assuming the author is not an employee, absent a written agreement to the contrary a company may not publish the work on the website or otherwise. If the submission was for bothprint and web, web publication would be permissible, per the guidelines in the next paragraph.If the work was submitted for publication on the web, and assuming the author is not an employee, absent a written agreement to the contrary that one-time use applies only to the web, the company may continue perpetually to host that page (with the article) on its site as it was originally published, including archiving. Here, “one-time use” means publishing the work on the publisher’s website as it would normally do initially on a web page. What the publisher may notdo is take the work off of that page and present it in other places, other compilations, other web pages, in print, etc.This guidance on length of publishing on the web applies to web submissions in any cases, including pursuant to written agreements or otherwise. It also would apply in cases pursuant to written agreements where works were submitted for publication in a print magazine with a proper grant of rights for electronic publishing.

F. Summary of Rights Status (by type of rights)

Add Comment