Privacy by Design refers to a design of technology that emphasizes privacy as its default setting and is proactive in its approach to building and ensuring privacy throughout the life cycle of data storage.

About twenty years ago, Ann Cavoukian, now Information & Privacy Commissioner of Ontario, Canada, coined the term “Privacy by Design” to address privacy concerns if (ever) law and regulation failed to protect consumer needs. Today, although some technologies are created in adherence to the core principles of Privacy by Design (PbD), many new product developments do not begin implementing privacy on Day 1. If this seemingly practical approach to privacy is, in fact, good practice, then why isn’t everybody doing it?

Some theories:

- Businesses do not fully appreciate consumer needs.

- Alternatively, while businesses do appreciate that default privacy could benefit consumers, businesses calculate that there is no actual demand for it, thus no need to supply.

- Alternatively, we (who no speak legalese) don’t know what’s really going on.

So what exactly is Privacy by Design?

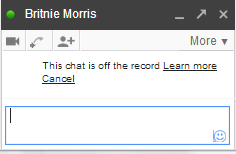

The option to go off the record in GChat is one example of Privacy by Design.

Put simply, PbD is built-in privacy. (A brief summary of the 7 Foundational Principles of Privacy by Design is included at the end of this post.) Dr. Cavoukian, who was recognized as the founder of Privacy by Design by the Best Practices Institute, identified default practices as a preventive solution to address the need for privacy, a need which she had anticipated. So, for example, the option to go “off the record” during a conversation in Google’s Gchat application illustrates PbD. Another example is 2-step security verification, used by companies such as Twitter and Evernote, which protects a user’s account against a third party discovering the user’s log-in information. PbD is not yet ubiquitous, but it is already incorporated into some of the products that many of us use every day. Nonetheless, at least according to the Future of Privacy Forum, a Washington, DC based think tank, businesses often struggle to implement Cavoukian’s principles into practice.

What do you want? Privacy. When did you want it?

Remember Buzz? Google’s long lost social media network? (Not many other people do either. See for example Molly Wood’s rant, “Google Buzz: Privacy Nightmare”.) According to Forbes, one of Buzz’s privacy shortcomings lay in the fact that a user’s prepopulated contact list was easily visible to others. Google’s latest social media venture, Google+, however, in allowing users to privately designate friends, family members, acquaintances and colleagues to specific “circles”, more broadly attempts to incorporate PbD concepts. Had Google better incorporated into Buzz an awareness that users’ privacy needs differed, maybe (but really, maybe) Buzz would have succeeded.

No demand, then why supply?

It was recently widely reported that Wal-Mart was undergoing an intense process of going green in an effort to save some … green. Although the retail giant might have chosen to adopt and market more environmentally-friendly practices years ago to woo eco-conscious consumers, Wal-Mart’s recent focus was strongly motivated by its bottom line. The Los Angeles Times reported that Wal-Mart was quite open in admitting that goodwill was simply a side benefit. It may be that although some businesses identify ways for product development to be more inherently private, without legal or financial compulsion to do this, why then spend the extra time and money?

Haven’t you read our terms of service? What terms of service?

Or perhaps everybody is doing it. (“I just did it and I’m ready to do it again”, in the immortal words of Mel Brooks’ Louis XVI in “History of the World (Part 1).”) Is it possible that consumers are just not aware of what’s going on? Last month, I attended Mediaite’s Summit on Privacy, Security, and the Digital Age. The discussion was held just weeks after news broke of Edward Snowden’s disclosures about the National Security Agency’s surveillance activities, and focused on the role of consumer privacy in both business operations and government regulation. Michael R. Nelson, Tech and Internet Policy Analyst at Bloomberg Gov, argued in Part 2 of the panel discussion that most of us (consumers) don’t really know what’s happening. Nelson believes that technologists might start embedding privacy within product and service designs if consumers are not made aware of the rules, or the law.

So there has to be some way to actually get rules out there so we know what’s actually going on… I think technologists might very well start creating their own structures that will do it for us. So we’ll get the encryption, we’ll get clouds that are protected and perhaps located in countries that aren’t gonna listen to the NSA… [T]here are ways to get this privacy (emphasis added) … using technology rather than regulation. – Michael Nelson quoted by Adam Thierer, The Technology Liberation Front

The “structures” to which Nelson refers sound a lot like PbD, right? Also, if Nelson is suggesting that consumers do not fully understand which privacy rights they should be afforded, it is certainly possible that companies may be going about their businesses without acknowledging regulation, especially if the law is not enforced.

Location services enabled and disabled in Facebook Chat Mobile.

By the same token, maybe consumers also lack knowledge about what businesses are doing in the way of default privacy. For a moment, let’s assume that the law is up to date and everyone is well informed of their rights. What good is this knowledge when, quite regularly, ancient Greek often reads easier than a Terms of Service agreement. Consumers can be forgiven for clicking “I agree” rather than trying to understand Facebook’s latest privacy update when all they want to do is see what’s happening in their social networks. Although sometimes these privacy updates explain new developments that actually do give users more privacy.

For example, a little arrow appears in the bottom right corner of the composition window when typing a tweet or sending a message using Facebook mobile. When highlighted, this arrow indicates that the user’s location is being shared. Whether or not these products (i.e. social media sites) offer much in the way of overall privacy, this feature is certainly another good example of PbD.

Nobody really has to do it.

Privacy by Design receives little criticism and, to a slightly informed eye, looks good on paper. It is safe to say that consumers would not be upset if PbD were widely adopted, but since consumers don’t demand it and the law currently doesn’t require it, it’s up to businesses to decide whether or not default privacy could benefit their business needs.

Here’s a brief summary of the 7 Foundational Principles of Privacy by Design:

1. Proactive, not Reactive; Preventative, not Remedial

• PbD anticipates and prevents so risks don’t become problems

• It does not include solutions because, by design, these should be prevented

2. Privacy as the Default

• Maximum privacy should insure protection of all personal data

• The individual doesn’t need to act because the privacy is built right in

3. Privacy Embedded into Design

• PbD is not an add-on but rather a part of the delivered product

• It is fundamentally embedded into design

4. Full Functionality – Positive-Sum, not Zero-Sum

• No false dichotomies or trade offs

• It doesn’t have to be either privacy or security- these can coexist

• All legitimate interests or objectives are considered- a win-win

5. End-to-End Lifecycle Protection

• Strong security from cradle to grave

• Secure lifecycle management of information- data is securely retained and destroyed

6. Visibility and Transparency

• Regardless of the industry, PbD operates according to specific standards

• All components of these standards remain visible to both users and providers

7. Respect for User Privacy

• Individuals’ interests should be catered to with set standards such as strong privacy defaults, appropriate notices and user friendly options

• Architects and operators should keep it user-centric

Andrew Mirsky, Principal with Mirsky & Company, PLLC, contributed to this post.

Add Comment